Elliott W. David

INTERVIEWS AND SUCH

Index

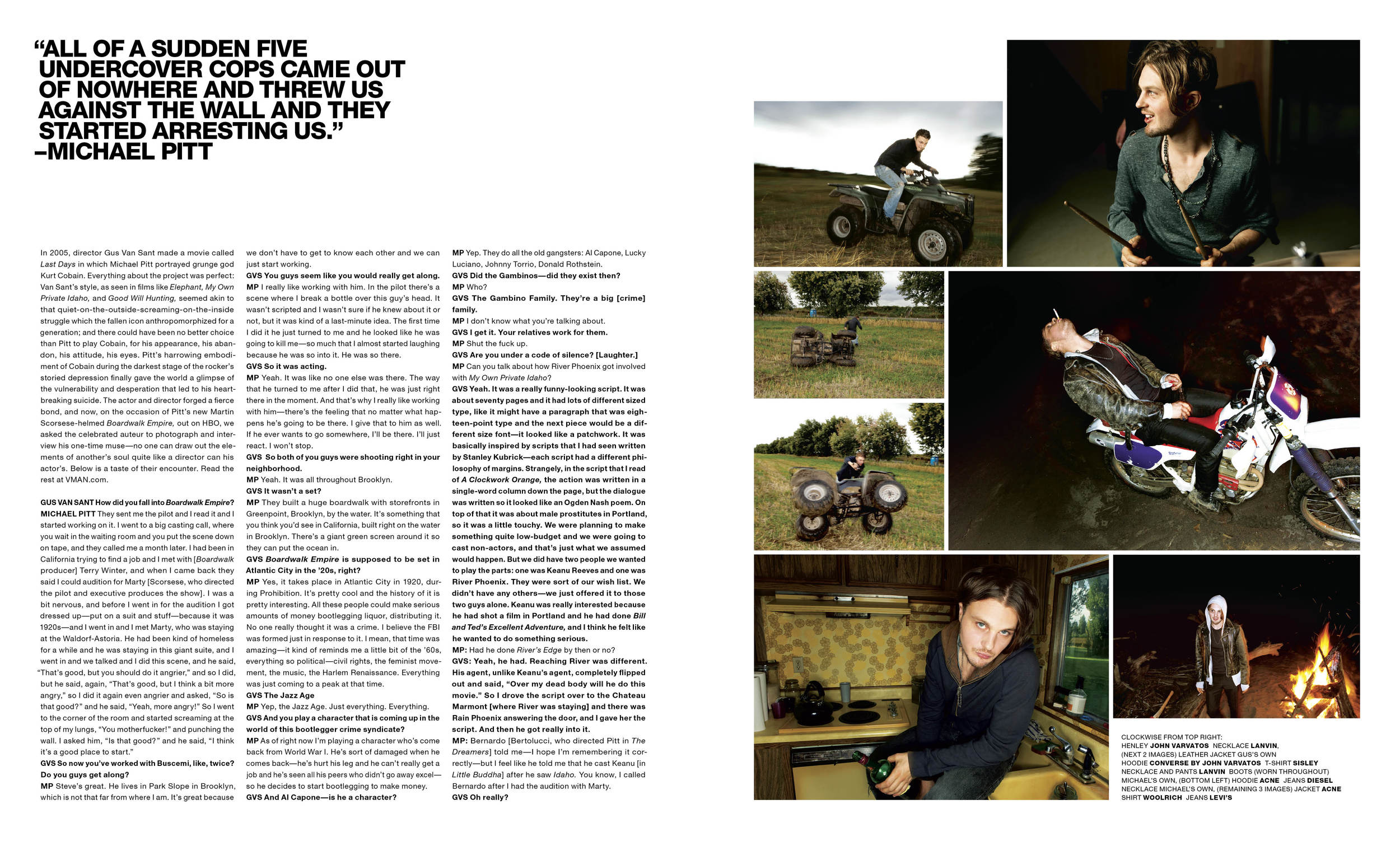

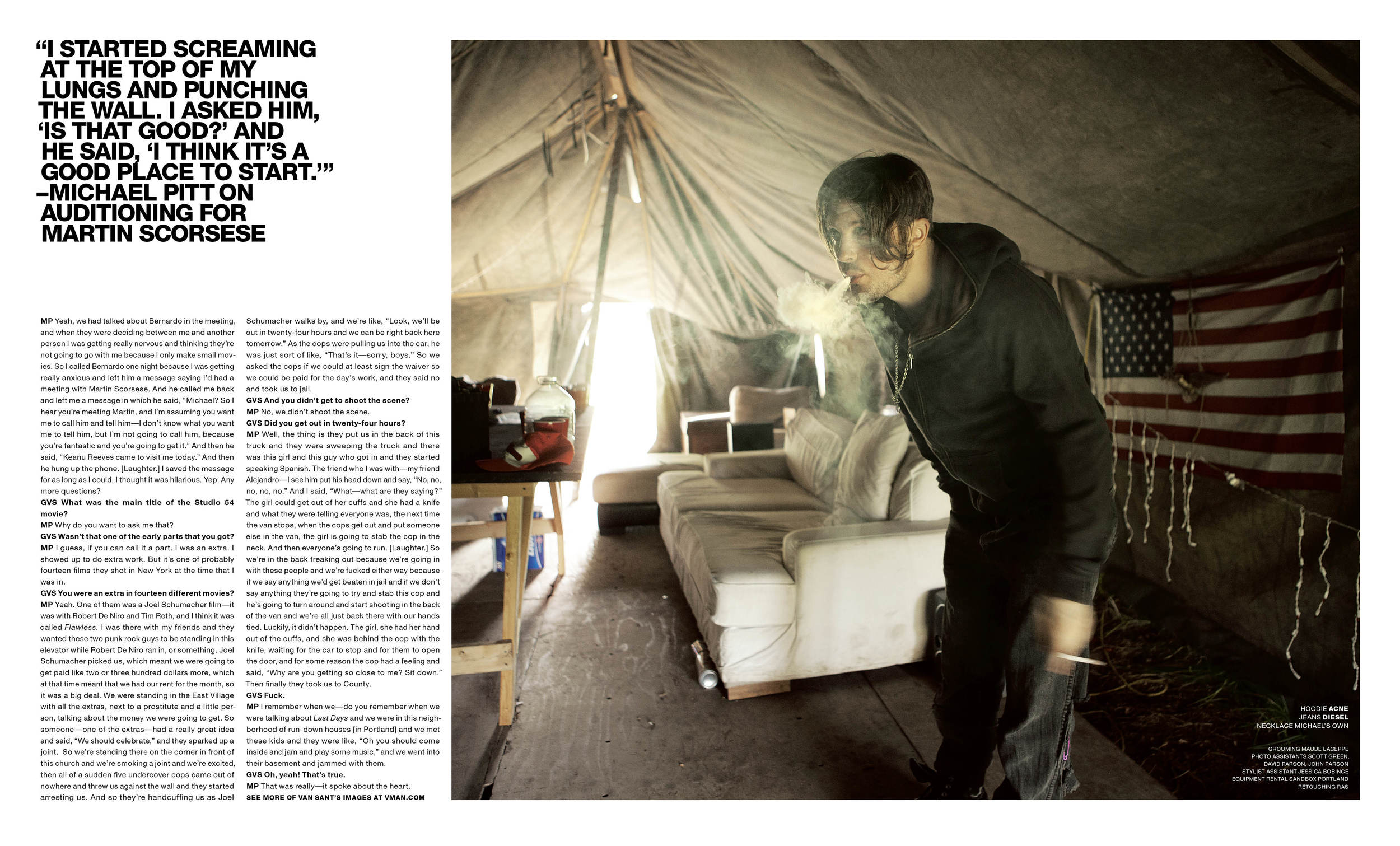

PHOTOGRAPHY AND INTERVIEW GUS VAN SANT

TEXT ELLIOTT DAVID

Michael Pitt sits down next to me and just starts speaking, slow and low. “I woke up in Bedstuy this morning and fed my cat. Then I took the subway up to midtown. Then I went to a writer’s meeting on this film I’m going to do called Rob the Mob. We worked for like four of five hours, then I went to Union Editorial to talk to the editors on this other movie I’m doing called You Can’t Win.” We’re sitting in the back of some restaurant in Williamsburg, unremarkable but thorough in that Brooklyn brand of bourgeois-bohemian rusticity. The old-timeyness is sort of suitable, since Pitt is probably most widely known for playing Jimmy Darmody in Martin Scorsese-incepted prohibition drama Boardwalk Empire. His character was killed off the show during the second season’s finale last year, but Pitt doesn’t sound wont for projects. He’s shrouded in layers of black on black on black, a loose tuque swallowing most of his head. The first thing I think of when he starts up is the same thing I thought about earlier and most of while I was waiting for him to get here: that the common thread in my attempts at research on him was a well reported aversion to the press. Added to the fact that he’d already rescheduled this thing like five times, it’s safe to say I was anticipating some static. Yet here he is, ready to talk about whatever, his exhaustion a muted giddiness, his face unraveled of the pugnacious, punked up expression I’ve seen him wear in films. He looks like a relaxed fist. “After all that I had an hour so went to the gym and boxed 12 rounds.” Then he went back to his studio in Bedstuy to work on a painting. Then he went to a writing session with the director Michael Cahill. Then he came to this restaurant, smiled, nodded, sat down next to me, and just started talking.

How it works is you have to invent yourself piece by piece. That’s the American way. Always has been. Still is. Countless men have known as much, some great and some unknown, and Pitt is arguably both of those things, as far as actors go. In his young career, the 31 year old has worked practically exclusively with the greatest living filmmakers. That’s less hyperbole than fact. To name a few: Larry Clark, Bernardo Bertolucci, Gus Van Sant (twice), Michael Haneke, and he just came off a part in the movie Seven Psychopaths by the Oscar-winning, Irish playwright Martin McDonagh—these guys are treasures of their respective nations. But on the list of famous actors that our moviegoing public unconsciously tallies in our collective brain, the same one the studio system spends billions trying to market watch—Pitt doesn’t hit the marquee. Which is exactly how he wants it, and he’s worked hard to get things this way.

He was fourteen when he first trekked to New York from his home of West Orange, NJ (pop. 46k) and “crashed” an acting class at the Academy for Dramatic Arts taught by Bill Barlett, whom Pitt has described as “one of his angels.” “Basically,” Pitt says, “Bill said, ‘I can’t teach you how to act. I can show you what I know, but really you should get the fuck out of acting class and just go do it.’ That’s oversimplifying it, but it was really valuable advice.” The prior events of Pitt’s life are fuzzy and he’s completely disinterested in sharing them, but he’s hinted that they were unpleasant. West Orange, by statistical and architectural accounts, seems to be an upper-middle class suburb in Essex county. But that doesn’t really mean anything. Pitt went to a series of high schools (reportedly with a stint at juvie) before dropping out at fifteen or sixteen and moved to New York, another broke kid dabbling in crust punk homelessness or cheap ass communal living, in hopes, like a huge percentage of everybody else, to somehow subsist on music or acting or art. “I sort of bummed around Manhattan when I didn’t really have an address,” he says. “When I moved to Brooklyn, it was a financial thing. Then I learned that there’s a lot of people in the same financial situation that I was in.” He’s been in Brooklyn ever since, coastally detached from Hollywood’s industrial heart. Which makes perfect sense, since the only thing more consistent than Pitt’s borough devotion is his disinterest in acting in any film that won’t challenge or progress him as an actor. This has been Pitt’s lone aspect of decision making. Not career. Definitely not money. Just an unwavering obedience to his unpurchasable artistic impulse.

Nowadays when he’s between parts, Pitt works out of his aforementioned studio, which takes up the top floor of an office building. “It’s basically three big rooms,” he says. “One room is a live recording studio, a full set up for a band. The middle room is sort of just computers, a control dock to record and to edit films and make prints. And the third room is just a place to paint and get together art.” Since the income from cherry-picking acting parts in independent cinema is, in a word, inconsistent, Pitt occasionally subsidizes with work in fashion. Like, for instance, right now: he’s this season’s face of Prada. “I’ve taken fashion campaigns and stuff like that to sort of support specific artistic endeavors, which is more comfortable for me [than film roles] because I’m not a model. One big reason, financially, that I’ve been able to live and pay rent in New York and wait for projects or the right director, has been doing things for the fashion industry. For all its vanity and superficialness, they actually do a lot: they raise so much money for organizations and support so many artist. That’s the truth of it.” Besides Prada, Pitt has worked with YSL and Vivienne Westwood, brands that would do nothing but propagate his arty cred. But this isn’t just now that he’s an incredibly famous actor, which he is. He’s been this way since the very beginning, his fearlessness powered by a single mentality, one that may grow organically in a teenage drop out aspiring artist scraping by in New York, but is far more challenging to maintain when you’re a successful adult: I’ve got nothing to lose.

But back to that beginning: Pitt’s first role was a performance of the Macarthur Genius-granted playwright Naomi Wallace’s The Trestle at Pope Lick Creek, for which he was paid $250 a week. The New York Times at the time described him as an “angelic blond [sic] teen-age boy.” After a performance, the then 19 year old Pitt was approached backstage by casting directors about auditioning for the breakout YA drama Dawson’s Creek, which had just finished airing its second season. Trestle opened in June of 1999. In October, Pitt made his Dawson’s debut as Henry Parker, freshman star quarterback and Michelle Williams love interest. In May, less than a year after Trestle opened and a month after Pitt turned 20, his final episode aired. He walked away from one of TV’s most successful shows. Thus began his lifelong trend of turning down employment.

“You’ve got to understand,” he says at the mere mention of Dawson’s. “I did that television show because it was my first job. But I also turned down a contract that has never been turned down before. Without any security or money in the bank, without any promise of a career. Not every actor does that. I think sometimes actors feel like they can’t say no. But hopefully they’ll read interviews like this and think they can. I saw actors making odd and very bold choices, and they sort of paved the way for me to say, No, this is how I want to do it.”

Then it sort of happened all at once. Right after he left Dawson’s (2000), Pitt got a small part in Gus Van Sant’s Finding Forrester. In 2001 he landed John Cameron Mitchell’s movie adaptation of the smash underground transgender musical, Hedwig And The Angry Inch, playing rockstar/dissociative identity Tommy Gnosis. Mitchell, who originally based the role of Tommy on himself, has said that beyond the personal difficulty in casting the part, it was coveted by established actors, of which Pitt was not. But he auditioned repeatedly and ultimately got it, because that’s how it sometimes works if you’re talented. That same year, Pitt worked with film’s ambassador of dark youth subculture, director Larry Clark, depicting a drug-blasted beautiful boy in the ennui-and-homicide pulp classic Bully. It would be his first of many on-screen kills. But it was his performance in Bertolucci’s The Dreamers that revealed Pitt’s visceral range and feral energy, declaring him a rare and unafraid talent, an invaluable addition to his generation of actors and meaningful contemporary cinema. And that’s right about when he evolved to the stage of turning down the Hollywood movies that could eventually make him millions of dollars. He just didn’t see the value in it.

“In retrospect, I’ve made pretty small films,” he says. “I’m learning to be a businessman, but film is not a business to me, it’s an art form. If I was thinking about money, I wouldn’t be doing the projects that I do. It’s as simple as that.” By rejecting the studio system, Pitt has kept himself out of the spotlight. But even if his films have had smaller budgets, most have yielded significant cultural value and a wealth of controversy. Nearly all his films have in their own way confronted mainstream moral codes, some of them expired and deserving (homophobia, racism) but some of them just sensical (don’t kill people for no reason). Even when Pitt reunited with Van Sant in 2005 for Last Days: I remember thinking that wasn’t there a pre-existing, silent agreement among everyone that Kurt Cobain was off limits? Lot’s of anticipatory cringing going on. But Last Days turned out to be an at once hilarious and touching meditation on the fatal mix of success cooked with addiction. And it was compellingly articulated through 97 minutes of Pitt barely speaking a word.

He played a far more vocal character, however, in Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, a story mostly guided by his character’s narration of its unrelenting sadism. For the unfamiliar, the long and short of it is two sociopaths cooly and by the grace of good manners invade a family’s home to murder them in a most dialectical fashion. To call that film scandalous would be redundant, since it was a near shot-for-shot remake of Haneke’s ‘97 Austrian original of the same name. Haneke, universally acknowledged one of the all time greats, at the time baffled fans in this decision, the original film a Palme d’Or nominated critique of the way our country romanticises and denatures violence. An instant classic. But in retrospect, it’s pretty clear that he wanted to make a Hollywood version so the American culture could more easily consume his criticism of it. It only seems fitting, then, that Pitt’s most mainstream film was literally designed to isolate him from it further.

Speaking about one of the most violent films ever seems like a good time to point out the fact that Pitt’s killed someone (or himself) in a vast majority of his roles. His career could be a study on the filmic expression of violence. “Really?” he says when I say this. “I want peace.” Come on, dude. “I think it’s a very violent world,” he says. “Turn on the fucking news. I certainly consider myself a very peaceful person, but I also think that sometimes the best way to avoid or to analyze something is to look it straight in the face. My films could be looked upon as violent, or Die Hard could be looked upon as violent. A big point that Michael Haneke made about violence in films is that it shouldn’t be pleasurable. People find it very hard to watch some of his films, and that’s the intention. There should be consequences, they should die at the end. There shouldn’t be a happy ending because in a lot of instances that’s the reality.”

And that’s what sets Pitt apart from most all other actors: some of us go to movies to escape reality, and some of us go to films to find a different understanding of it. Pitt deals exclusively in the latter. “Anyone who works on something, they want to show it,” he says. “But do I want everyone to see it? It’s more important to me that the right people see it.” So, in keeping with his m.o., right after Games, in which Pitt delivered a harrowing performance alongside Naomi Watts and Tim Roth, if ever there would be a time for him to embrace artistic filmmaking on a mainstream level, that would be it, regardless of that other shit I said. So naturally he quit acting for two years. “I wasn’t even really interested in working at the time that [Funny Games] was happening. But I did this work session with [Haneke] and I was like, if I listen to what this guy tells me to do, he’s going to make me a better actor. And I’d worked enough to know that that doesn’t come around very often.”

He didn’t act after Games for the same reason he didn’t act any of those other times he didn’t act. Instead, he invested everything he had in himself. He read, wrote, painted, and played music with his band, Pagoda. “ I recorded two albums and directed and shot about 12 videos,” he says. “It’s been a lot of work. I wasn’t just sitting on my ass.” After two years of exhausting his option to stay broke by turning down any modest exploitation of his hard earned and highly respectable career, he heard about Boardwalk and got a meeting with Scorsese (to which he wore a borrowed suit from Armani). That project has ended, but this time he’s not holding out for anyone but himself. “To be just an actor is basically to wait for someone to write or direct [a film] that’s perfect for you. And then you do what you do, right? I don’t wanna wait.”

“There are actors who are just actors,” he continues. “I’m interested in the arts. It sounds cheesy, but I’ve always been interested in everything, which kind of manifests itself into filmmaking because it’s a medium that tackles literature, photography, image, music—it’s everything in one. I don’t separate them. These are just things that I have been drawn to. It’s my life. It’s my routine.”

For his upcoming films he’s either starring in, writing, producing, or all three. His short films and music are coming out when he feels they’re finished and finds the right way to share them. He has inventing a profitable and autonomous life through a series of tasteful projects with legendary creatives, all while maintaining a staunch unwillingness to sacrifice personal interest for a paycheck. It turns out that Michael Pitt is this paragon of the American Dream for the millennial generation, in that he gets to do whatever the fuck he wants.

“I’m blessed,” he says. "Yeah it’s a lot, me saying what I did today from beginning to end—it’s a lot, and it doesn’t end here. From here I’ll go back to screen a film. I’m fucking blessed to be able to do all these things. So I’m not gonna complain.”

—

In 2005, director Gus Van SanT made a movie called Last Days in which Michael Pitt portrayed grunge god Kurt Cobain. Everything about the project was perfect: Van Sant's style, as seen in films like Elephant, My Own Private Idaho, and Good Will Hunting, seemed akin to that quiet-on-the-outside-screaming-on-the-inside struggle which the fallen icon anthropomorphized for a generation; and there could have been no better choice than Pitt to play Cobain, for his appearance, his abandon, his attitude, his eyes. Pitt's harrowing embodiment of Cobain during the darkest stage of the rocker's storied depression finally gave the world a glimpse of the vulnerability and desperation that led to his heartbreaking suicide. The actor and director forged a fierce bond, and now, on the occasion of Pitt's new Martin Scorsese-helmed Boardwalk Empire, out on HBO, we asked the celebrated auteur to photograph and interview his one-time muse—no one can draw out the elements of another's soul quite like a director can his actor's.

GUS VAN SANT How did you fall into Boardwalk Empire?

MICHAEL PITT They sent me the pilot and I read it and I started working on it. I went to a big casting call, where you wait in the waiting room and you put the scene down on tape, and they called me a month later. I had been in California trying to find a job and I met with [Boardwalk producer] Terry Winter, and when I came back they said I could audition for Marty [Scorsese, who directed the pilot and executive produces the show]. I was a bit nervous, and before I went in for the audition I got dressed up-put on a suit and stuff-because it was 1920s-and I went in and I met Marty, who was staying at the Waldorf-Astoria. He had been kind of homeless for a while and he was staying in this giant suite, and I went in and we talked and I did this scene, and he said , "That's good, but you should do it angrier," and so I did, but he said, again, "That's good, but I think a bit more angry," so I did it again even angrier and asked, "So is that good?" and he said, "Yeah, more angry!" So I went to the corner of the room and started screaming at the top of my lungs, "You motherfucker!" and punching the wall. I asked him, "Is that good?" and he said, "I think it's a good place to start."

GVS So now you've worked with Buscemi, like, twice? Do you guys get along?

MP Steve's great. He lives in Park Slope in Brooklyn, which is not that far from where I am. It's great because we don't have to get to know each other and we can just start working.

GVS You guys seem like you would really get along.

MP I really like working with him. In the pilot there's a scene where I break a bottle over this guy's head. It wasn't scripted and I wasn't sure if he knew about it or not, but it was kind of a last-minute idea. The first time I did it he just turned to me and he looked like he was going to kill me-so much that I almost started laughing because he was so into it. He was so there.

GVS So it was acting.

MP Yeah. It was like no one else was there. The way that he turned to me after I did that , he was just right there in the moment. And that's why I really like working with him-there's the feeling that no matter what happens he's going to be there. I give that to him as well. If he ever wants to go somewhere, I'll be there. I'll just react. I won't stop.

GVS So both of you guys were shooting right in your neighborhood.

MP Yeah. It was all throughout Brooklyn.

GVS It wasn't a set?

MP They built a huge boardwalk with storefronts in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, by the water. It 's something that you think you'd see in California, built right on the water in Brooklyn. There's a giant green screen around it so they can put the ocean in.

GVS Boardwalk Empire is supposed to be set in Atlantic City in the '20s, right?

MP Yes, it takes place in Atlantic City in 1920, during Prohibition. It's pretty cool and the history of it is pretty interesting. All these people could make serious amounts of money bootlegging liquor, distributing it. No one really thought it was a crime. I believe the FBI was formed just in response to it. I mean , that time was amazing-it kind of reminds me a little bit of the '60s, everything so political-civil rights , the feminist movement, the music, the Harlem Renaissance. Everything was just coming to a peak at that time.

GVS The Jazz Age

MP Yep, the Jazz Age. Just everything. Everything.

GVS And you play a character that is coming up in the world of this bootlegger crime syndicate?

MP As of right now I'm playing a character who's come back from World War I. He's sort of damaged when he comes back-he's hurt his leg and he can't really get a job and he's seen all his peers who didn't go away excel, so he decides to start bootlegging to make money.

GVS And AI Capone-is he a character?

MP Yep. They do all the old gangsters: AI Capone, Lucky Luciano, Johnny Torrio, Donald Rothstein.

GVS The Gambinos, did they exist then?

MP Who?

GVS The Gambino Family. They're a big [crime] family.

MP I don't know what you're talking about.

GVS I get it. Your relatives work for them.

MP Shut the fuck up.

GVS Are you under a code of silence?

MP Can you talk about how River Phoenix got involved with My Own Private Idaho?

GVS Yeah. It was a really funny-looking script. It was about seventy pages and it had lots of different sized type, like it might have a paragraph that was eighteen- point type and the next piece would be a different size font-it looked like a patchwork. It was basically inspired by scripts that I had seen written by Stanley Kubrick—each script had a different philosophy of margins. Strangely, in the script that I read of A Clockwork Orange, the action was written in a single-word column down the page, but the dialogue was written so it looked like an Ogden Nash poem. On top of that it was about male prostitutes in Portland, so it was a little touchy. We were planning to make something quite low-budget and we were going to cast non-actors, and that's just what we assumed would happen. But we did have two people we wanted to play the parts: one was Keanu Reeves and one was River Phoenix. They were sort of our wish list. We didn't have any others-we just offered it to those two guys alone. Keanu was really interested because he had shot a film in Portland and he had done Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure, and I think he felt like he wanted to do something serious.

MP: Had he done River's Edge by then or no?

GVS: Yeah, he had. Reaching River was different. His agent, unlike Keanu's agent, completely flipped out and said, "Over my dead body will he do this movie." So I drove the script over to the Chateau Marmont [where River was staying] and there was Rain Phoenix answering the door, and I gave her the script. And then he got really into it.

MP: Bernardo [Bertolucci, who directed Pitt in The Dreamers] told me—l hope I'm remembering it correctly—but I feel like he told me that he cast Keanu [in Little Buddha] after he saw Idaho. You know, I called Bernardo after I had the audition with Marty.

GVS Oh really?

MP Yeah, we had talked about Bernardo in the meeting, and when they were deciding between me and another person I was getting really nervous and thinking they're not going to go with me because I only make small movies. So I called Bernardo one night because I was getting really anxious and left him a message saying I'd had a meeting with Martin Scorsese. And he called me back and left me a message in which he said, "Michael? So I hear you're meeting Martin, and I'm assuming you want me to call him and tell him-1 don't know what you want me to tell him, but I'm not going to call him, because you're fantastic and you're going to get it." And then he said , "Keanu Reeves came to visit me today." And then he hung up the phone. [Laughter.] I saved the message for as long as I could. I thought it was hilarious. Yep. Any more questions?

GVS What was the main title of the Studio 54 movie?

MP Why do you want to ask me that?

GVS Wasn't that one of the early parts that you got?

MP I guess, if you can call it a part. I was an extra. I showed up to do extra work. But it's one of probably fourteen films they shot in New York at the time that I was in.

GVS You were an extra in fourteen different movies?

MP Yeah. One of them was a Joel Schumacher film—it was with Robert De Niro and Tim Roth, and I think it was called Flawless. I was there with my friends and they wanted these two punk rock guys to be standing in this elevator while Robert De Niro ran in, or something. Joel Schumacher picked us, which meant we were going to get paid like two or three hundred dollars more, which at that time meant that we had our rent for the month, so it was a big deal. We were standing in the East Village with all the extras, next to a prostitute and a I ittle person, talking about the money we were going to get. So someone—one of the extras—had a really great idea and said, "We should celebrate," and they sparked up a joint. So we're standing there on the corner in front of this church and we're smoking a joint and we're excited, then all of a sudden five undercover cops came out of nowhere and threw us against the wall and they started arresting us. And so they're handcuffing us as Joel Schumacher walks by, and we're like, "Look, we'll be out in twenty-four hours and we can be right back here tomorrow." As the cops were pulling us into the car, he was just sort of like, "That's it. Sorry, boys." So we asked the cops if we could at least sign the waiver so we could be paid for the day's work, and they said no and took us to jail.

GVS And you didn't get to shoot the scene?

MP No, we didn't shoot the scene.

GVS Did you get out in twenty-four hours?

MP Well, the thing is they put us in the back of this truck and they were sweeping the truck and there was this girl and this guy who got in and they started speaking Spanish. The friend who I was with-my friend Alejandro-! see him put his head down and say, "No, no, no, no, no." And I said, "What-what are they saying?" The girl could get out of her cuffs and she had a knife and what they were telling everyone was, the next time the van stops, when the cops get out and put someone else in the van, the girl is going to stab the cop in the neck. And then everyone's going to run. [Laughter.] So we're in the back freaking out because we're going in with these people and we're lucked either way because if we say anything we'd get beaten in jail and if we don't say anything they're going to try and stab this cop and he's going to turn around and start shooting in the back of the van and we're all just back there with our hands tied. Luckily, it didn't happen. The girl, she had her hand out of the cuffs , and she was behind the cop with the knife , waiting for the car to stop and for them to open the door, and for some reason the cop had a feeling and said, "Why are you getting so close to me? Sit down." Then finally they took us to County.

GVS Fuck.

MP Do you remember when we were talking about Last Days and we were in this neighborhood of run-down houses [in Portland] and we met these kids and they were like, "Oh you should come inside and jam and play some music," and we went into their basement and jammed with them.

GVS Oh, yeah! That's true.

MP That was really—it spoke about the heart.