Elliott W. David

INTERVIEWS AND SUCH

Index

GURU 3.0

TEXT ELLIOTT DAVID

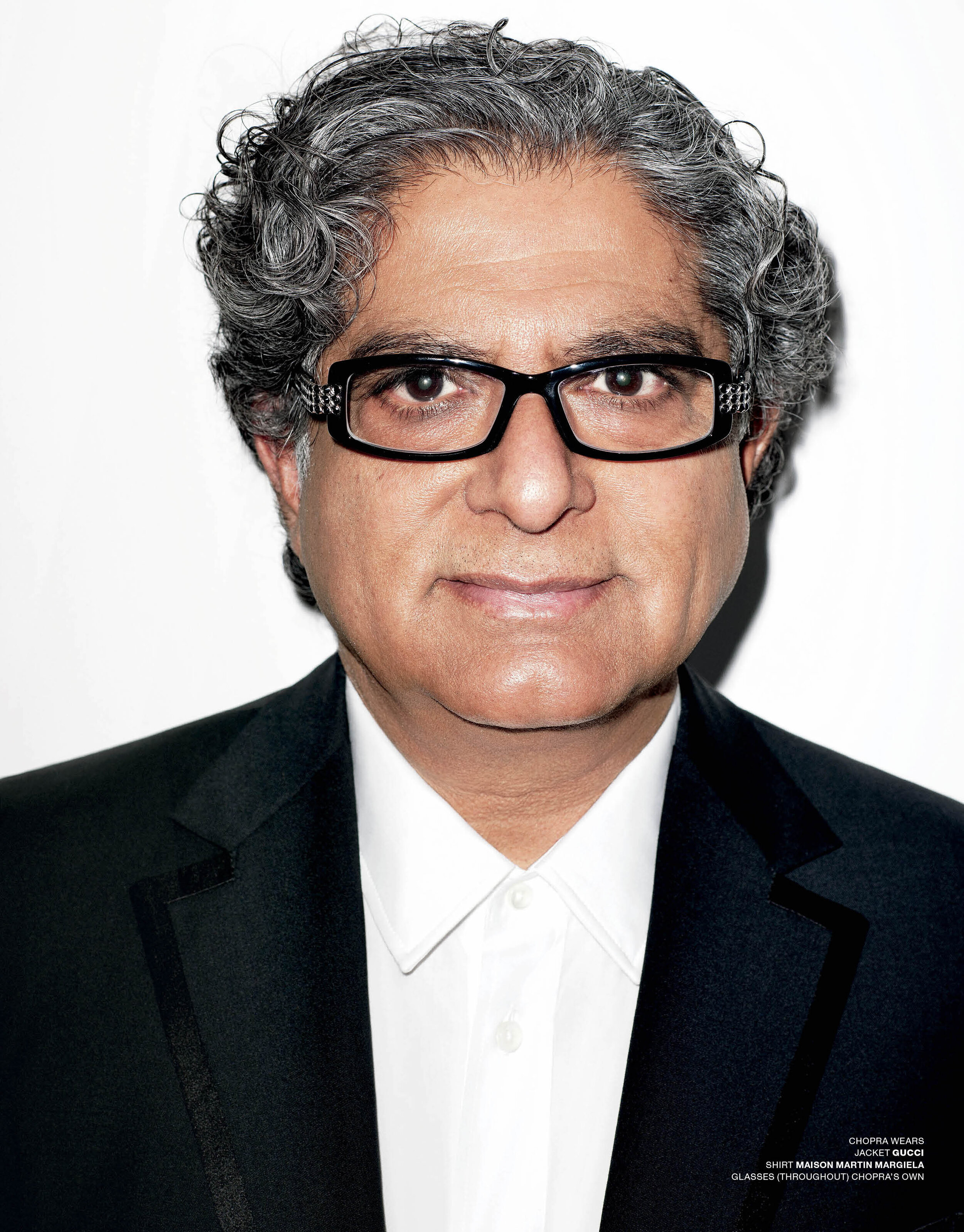

DEEPAK CHOPRA IS ONE OF THE MOST PROMINENT AND POLARIZING FIGURES OF THE PAST CENTURY. FOR OVER 30 YEARS, HE’S RECEIVED BOTH TREMENDOUS PRAISE AND HARSH CRITICISM VOICED BY SOME OF OUR GREATEST LIVING MINDS. REGARDLESS OF WHERE YOU STAND, FOR A GROUP OF TROUBLED KIDS IN NEW YORK CITY, CHOPRA’S URBAN YOGIS PROGRAM HAS PROVIDED SOMETHING LIKE SALVATION.

Contemplating the nature of existence is as old as consciousness itself. Evidence of religion dates back to the earliest records of written language and the development of computable knowledge, but likely originated with oral language, if not mere sentience. Some ideas have lasted millennia: The I Ching originated in 2200 bce. Ontological notions that date back to 500 bce are similar to those being explored today on a particle level. A 2010 Gallup poll stated that 40 percent of Americans are still strict creationists who believe god invented humans 10,000 years ago—that’s four out of every ten people. Some beliefs have been entirely disregarded—few still pray to Zeus—while others are recent inventions, like humanism and Scientology. The array of nuanced metaphysical, epistemological, and supernatural ideologies devised by humans are more than any one person can fully comprehend in a lifetime. But Deepak Chopra has nevertheless attempted to do so.

After moving to the States from New Delhi, in 1970, to study internal medicine and endocrinology, Chopra ultimately became the Chief of Staff at New England Memorial Hospital. In 1985, after meeting the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the mind behind Transcendental Meditation, Chopra left the hospital to pursue a less mechanistic, more alternative, holistic approach to medicine. After beginning with a focus on Ayurvedic treatments—a Hindu system of medicine based on a mind-body homeostasis achieved through diet, herbs, and yoga, among other things—Chopra would a decade later part ways with the Maharishi and become something of a spiritual polymath. In 1996, he founded the Chopra Center for Well Being, which offers a “holistic view of life that sees human beings as networks of energy and information, integrating body, mind, and spirit.” Chopra built up a legion of powerful and famous followers, and in the process authored over 70 books in more than 85 languages, 20 of which are New York Times best sellers, ultimately becoming an international celebrity. Through various means of commercialism, Chopra has become a millionaire many times over. He has been the recipient of both support and criticism across many fields in the sciences and the humanities—skeptics and zealots, quantum physicists and religious fundamentalists alike—each side voiced by some of our greatest living minds. He is one of the most prominent and polarizing figures of the past century.

Chopra, who often works in conjunction with other specialists, plays the role that any so-called guru should (or could) in the year 2014. He’s an international brand whose goal is to promote health and wellness, his ideas consisting of a combination of ancient philosophies—he does not believe in the supernatural and has said that at least 80 percent of old healing traditions are superstition that need to be discarded—and modern understanding of cosmology, biology, physics, evolution, and “the role consciousness plays in evoking biological responses.” Chopra has defined “God” as “the evolutionary impulse of the universe,” spirituality as “self-awareness and awareness of other people’s needs,” and “spirit,” he says, is synonymous with consciousness, “a domain of awareness where we can experience our universality.” He has also stated he believes that consciousness is the product of a universe evolving to a point where it can acknowledge itself.

Chopra’s recent writings focus on the emerging forms of study that can provide empirical data on the benefits of some holistic practices. Epigenetics, or the study of how external factors activate or inhibit gene expression, suggests that our DNA doesn’t just happen to us, and things as simple as diet and exercise can actuate advantageous genes and keep any predispositions for disease dormant. Neuroplasticity is a theory that the brain is not static and can be rewired or even healed, which the pracice of meditation has been shown to demonstrate with increasing clinical certitude. A team of Harvard-affiliated researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital found that people who took a mere eight-week course in mindful meditation displayed increased gray-matter density in structures of the brain associated with learning, memory, self-awareness, compassion, and introspection. The resultant reductions in stress—a benefit of meditation long evident anecdotally—were correlated with decreased gray-matter density in the amygdala, which is known to play a crucial role in anxiety and stress. These emergent fields can potentially serve to validate what has long been criticized or dismissed as overly spiritual or New Agey.

Some in the scientific community, certainly the positivists, resent having their fields interpreted (and sold) to the public in application to a philosophical agenda or anything a priori, no matter how well-intentioned. But often what can begin as high-minded dialogues, ranging from cosmology to diet, the health-care system to metaphysics, often become reduced to debates about Chopra himself, his terminology, semantics, capitalism, and ethics—with the occasional legal battle.

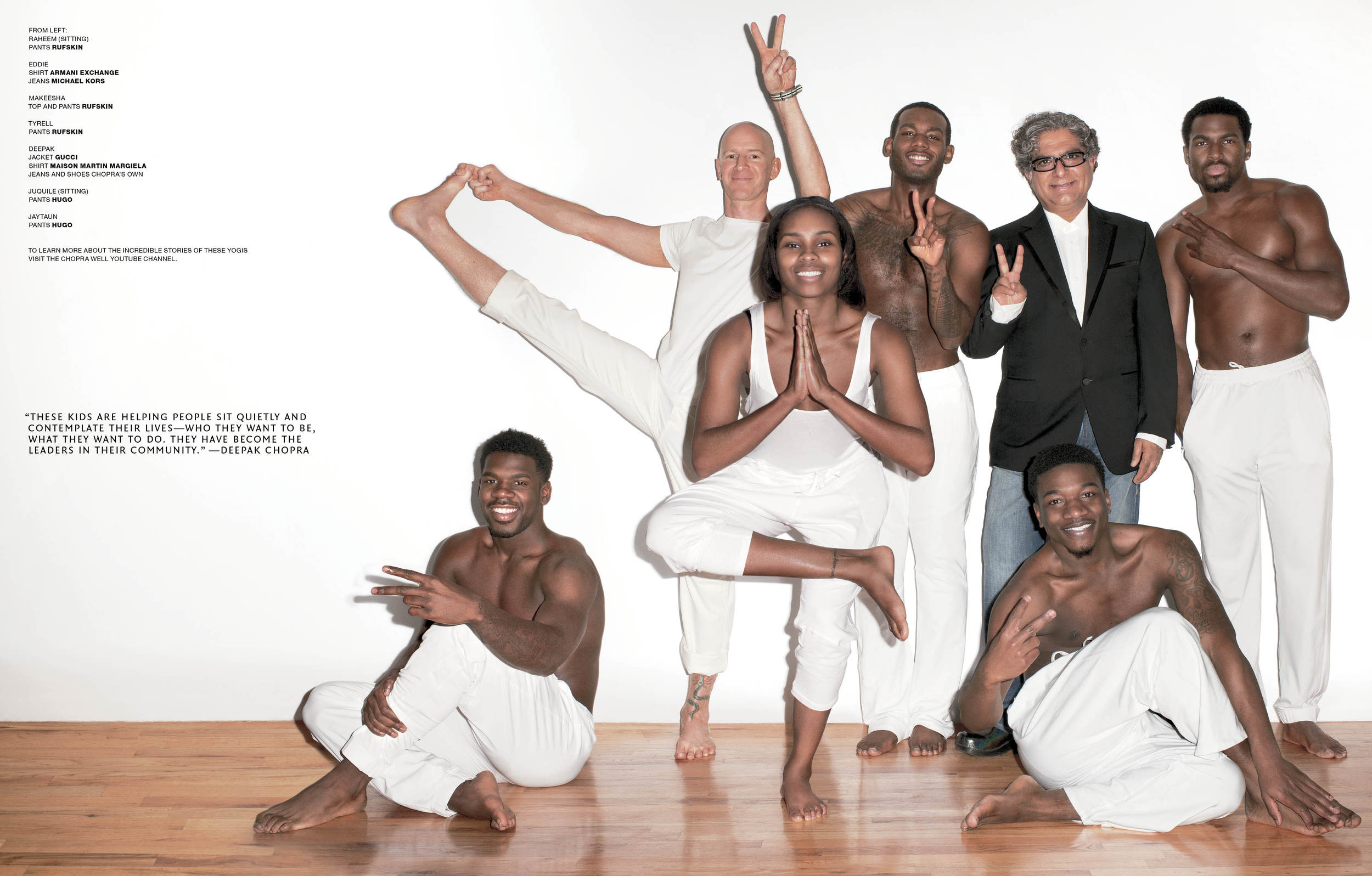

But despite all the discourse, at some point you have to quantify one’s spiritual or religious agenda by the tangible effects it has had on the world, a sort of extrinsic finality that has nothing to do with divinity, but rather concrete actions that have enacted positive change. And Chopra, at the very least, deserves respect for some of his results, such as the Urban Yogis program, a means by which Chopra and his yoga teacher, Eddie Stern, have helped a group of kids with troubled upbringings overcome their hardships, become leaders in their community, and lower acts of violence by teaching forms of meditation and yoga. To discuss this program and a world of other topics, Chopra sat down to casually chat about the universe over coffee.

ELLIOTT DAVID So let’s talk about those kids we were just with. When did the idea of developing this Urban Yogis program begin?

DEEPAK CHOPRA About three years ago I met Ericka Ford, an African-American woman in her 40s who works with families of children who’ve been killed in violence. She asked me if I could come speak to the kids and teach them mindfulness or meditation or anything. So I started going there once a week, and, slowly, I began to teach them meditation and contemplative technologies—you might say contemplative discipline. We are almost in year three now, and these boys and girls are now certified yoga teachers, and they’re employed by many schools to come and teach yoga and breathing techniques. They’re helping people sit quietly and contemplate their lives—who they want to be, what they want to do. The program is called Urban Yogis. It just happened by itself.

ED I know that other groups have had a lot of success by bringing some forms of meditation to troubled schools, like the David Lynch Foundation. Have you seen a lot of results?

DC What happened is the crime rate has gone down in that particular neighborhood by over 90 percent. The deaths were totally senseless. One kid shot a few people on a bus, and when they asked him why he said, “I didn’t like the way they were looking at me.” There are rival gangs who will just come and shoot people senselessly. When these kids started doing yoga, they said that a lot of other gangs and kids would come by and say they were sissies, that they were gay, and so on. But these kids continued, and now they have become literally the leaders in their community. They are also developing their own music label, a kind of hip-hop, yoga type of thing. We’re trying to get them their own merchandising on their label, on their clothes. They’re also teaching at the Harlem Village Academy. We want to take it nationwide.

ED How do you feel the addition of yoga differs from or enhances meditation on its own—what is gained or lost in combining the practices?

DC I think you need a balance of activity and stillness. If you have all stillness, people start to get flakey, tune-out, space-out even. I think yoga and meditation go together, and these kids are naturally athletic and like to move, so it’s a great outlet for them, especially because we combine it with music that they create on their own. They write their lyrics. You have to hear it.

ED I feel like it’s so necessary to teach kids how to be still and unplugged, particularly a generation growing up in a world where so much of identity is projected digitally. I’ve been practicing some form of meditation on and off since I was in my teens—biofeedback, mindfulness, etcetera—but this year I began transcendental meditation. Six months into it, I’d never felt more fully myself, highly resistant to stress and anxiety. I love it because it’s more of a biohack than anything spiritual. My point is that the tangible results are undeniable and invaluable, I cherish that time very much, and yet it’s still a challenge to get myself to fucking do it, to turn away from technology and just shut my eyes.

DC The contemplative traditions—it’s not just meditation, it’s self-reflection, it’s self-awareness, self-observation, it’s transcendence, it’s being an observer of your choices, it’s also questioning your perceptual reality as fundamental. Now, just realize the human species has been around for 100,000 years, oral language 15,000 years, written language has been around for 5,000 years, so as a species we’re probably not even adolescent yet. If you look back historically you find these amazing people, Plato, Parmenides, Socrates, some of the mythical prophets of the Old Testament, not all of them, anyone who could write the Psalms of Solomon, the Buddha, Confucius, it’s actually only a handful of people. We have a tendency to romanticize an ancient, glorified state of civilization. It was even more barbaric than today, even though our capacity to be barbaric has increased, thanks to technology and science, but human beings have been barbaric. Other animals, they kill to eat. We kill because of ideas. All the wars in the world are ideological wars. So there is something very strange about our species. It’s barbaric, it loves to kill. The history of the United States has never been peaceful, from the War of Independence to right now, there’s been a war going on. Now it’s taken for granted that war is a normal state. “These drones are okay.” With all this digital stuff I tell myself, and other people also, you have to parcel out your time: so there’s sleep time, there’s meditation time, there’s playtime, there is mindful eating time, there’s relationship time, there is work time, and there is digital time.

ED Right, digital time isn’t all of those times.

DC It shouldn’t be. This we know now for sure, that multitasking is one of the things that gets worse with practice and it ruins the neural networks in your brain. You’re sending confused messages to your brain. You ask an athlete to multitask, they can’t do it, because they are so focused, disciplined.

ED Have you read the theory that each person is only capable of so much discipline in a day, that willpower or self-control is a limited resource and it’s replenished through sleep? This is a psychology of habits kind of thing—you expend so much self-control on meditation time or mindful eating time or not having a cigarette time, then at night, you’re like, Oh, yeah, I should absolutely have four glasses of scotch. It’s like this daily zero-sum game.

DC There may be something to that. I think it’s okay for people to once and a while let loose and indulge. But there are certain personalities who can’t do that. They are either all or nothing, you know? I think that’s why it has to be on an individual basis. I think there is something to be said for those people who say, “It’s Friday, let’s go celebrate.”

ED Okay, so regarding the nature of addiction, how some people become dependent—or are using with that sort of frequency—but can be exposed to loss or trauma or have some epiphany and decide, This is terrible, time to stop now, and they stick to it, either on their own or through some program. But then there are people who just physiologically do not have that option, or it is such an insurmountable task that a massive chunk of their life and energy becomes devoted to not doing something. Maybe it’s genetic, maybe its situational, but obviously self-control is an issue there, so how do you scale the practice of yoga or mindfulness or meditation for them?

DC First of all, addiction is the number one issue of our civilization. Here’s the thing: I believe that, particularly for addiction to drugs and alcohol, it’s a memory of pleasure. The first time or first few times that you take it, it leaves an impression. You are hooked to the memory of pleasure. Even after the pleasure has exhausted itself, you’re still hooked to the memory. You can’t get enough of what you don’t want anymore. It’s a huge problem. I’ve worked with addicts all my life. I used to work at the VA Hospital in Boston when I was a resident [Chopra supervised the addiction unit], and I myself loved to drink, I used to smoke—so I have a lot of empathy for people who are struggling with this. I also know that a memory of intense pleasure or any intense emotion can never be erased. You cannot erase memory.

ED Right, nor can you trust it. There have been so many studies on how most memories are unreliable and outright self-deceiving. They say that because memories are processed so deeply and effortlessly, and recalled with such ease, that we trust them implicitly. But we don’t experience the distortion of memories after they’re stored. Assuming you even believe memories exist in the first place, which many people would argue they do not.

DC Well, they are stored in a nonlocal domain, yes. They are not erasable. So, what can you do? Well, the only thing you can hope for is to create a new memory, which is equally pleasurable and overshadows the old one. That’s a tough thing, because the addictive substance is so easy and so immediate. You get your kick, or your high right away. That thing for a lot of people is intense exercise. For a lot of people it’s yoga and all of that. For some, it’s meditation. Good enough! It’s keeping you healthy.

ED That was my logic. After I quit some more, shall we say, deleterious behaviors, I supplanted one addiction with that of health and exercise. But it was no less of an addiction. I was cutting off all the other aspects of my life, other people, other friends. It took me a while to be able to quit that as well and find a life of moderation. But at the time, people close to me would always say, “This is no different.” And I’d be like, “Well, it’s better.”

DC It’s better, but it is no different. I became an addict of writing and reading, exploring consciousness.

ED So do you think that sort of grasping and filling the void just is the nature of people?

DC In Eastern wisdom traditions, to go back to my tradition, everybody’s an addict—we wouldn’t incarnate into this life if we weren’t addicted to it. So the fact that we’re here is because we have an addiction. Enlightenment is that process where you slowly move from addictions to what you call attachments, and then from attachments to preferences, and then from preferences to intentions, then from intentions to subtle intentional choice. Finally to choiceless awareness, which means you’re free.